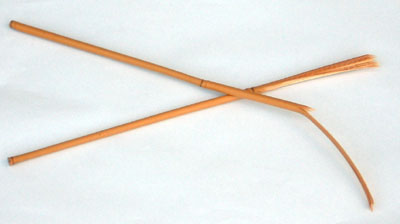

Photograph: Canes were a common instrument

used to instil corporal punishment.

Corporal punishment in Queensland state schools was a constant problem for educational administrators from the inception of the Queensland system of education in 1860 to its abolition in 1995. While the law did not change to any great extent during those years, the regulations of the Department of Education progressively restricted the use of corporal punishment. Some teachers disregarded these regulations.

Until the 1970s, the consensus of opinion in the Queensland educational field was that corporal punishment was a necessary evil to be used as a last resort. The consensus of public opinion accepted this viewpoint, with discontent directed mainly at violations of the regulations.

In 1992 a decision was made to phase out corporal punishment. At the beginning of the 1995 school year, corporal punishment in Queensland state schools was abolished.

The information on this pages comes directly, with minor editing and updating, from the publication Corporal punishment in Queensland State Schools, written by Eddie Clarke, an employee of then Education History Unit of the Queensland Department of Education. It was originally published in February 1980 as No.1 in the series Historical perspectives on contemporary issues in Queensland education.

Corporal punishment in the theories and methods of teaching

For about 25 years after 1885 the major text used in Queensland on the methods of teaching was

School Method of F.J. Gladman. This book and a larger but less popular volume by the same author,

School Work, made specific reference to the use of corporal punishment. Gladman stated that corporal punishment was the worst and therefore the last means to be used in the correction of children. He maintained that it had been used frequently and severely in the past but teachers were now endeavouring to do without it [F.J. Gladman,

School Work, Jarrold and Sons, 6th edn, London, 1904, p.69].

Gladman believed that corporal punishment was appropriate for such offences as immorality, falsehood, bullying, cruelty, habitual carelessness, obstinacy and wilful disobedience. He advised teachers that, when they did resort to corporal punishment, one or two stripes on the hand with the cane was sufficient. The teacher was thus able to see the physical effect produced. A hard unyielding instrument such as a ruler should never be used. Teachers should not strike pupils on the head or box their ears. Furthermore, it was wise usually to use corporal punishment privately. This precluded mock heroism on the part of the pupil or, worse, a stand-up fight with a pupil in front of the others, a situation which could prove damaging to the teacher's authority. Such private punishment was also believed to have a more salutary effect on the rest of the class. Gladman suggested that a teacher should keep some check upon himself by entering in a book the names of those punished and their offences [F.J. Gladman,

School Method, Jarrold and Sons, n.d., London, 1904, p-.171].

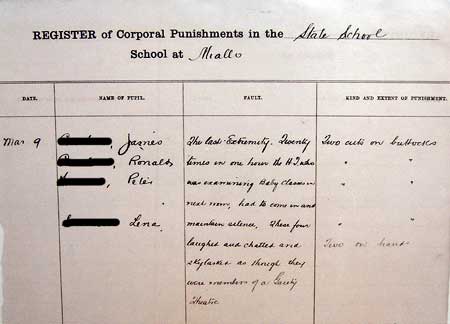

Photograph: A page extract from a register of corporal punishments (1936).

J. Landon, the author of a similar textbook used in Queensland during the same period, gave a more detailed commentary on the subject. In addition to comments similar to those made by Gladman, Landon included the following informative points. Pain was an inefficient form of punishment which frequently was wasteful of nervous energy, had a weakening effect, built up hatred and also hardened pupils to its use so that it became less effective. Many skilled teachers could do without it except on extraordinary occasions, but less capable teachers were more dependent upon it. Unfortunately, the problem of handling a large number of pupils drove some teachers to make use of corporal punishment. Though some schools had given up using the cane, other forms of bodily pain had been substituted, for example kneeling on the floor, supporting weights for a long time and being goaded by sharp points. It was better for the head teacher alone to inflict corporal punishment. This would ensure that it was in the hands of an experienced teacher whose uniform standard of punishment would be more readily accepted by the pupils. A cane was the best instrument to use and it should be kept out of sight. No good teacher walked around with a cane in his hand [J. Landon,

School Management, Kegan Paul, Trench & Co., London, 1887, pp.349–60].

From about 1914 to the late 1940s, the standard text on school method in Queensland was

The Suggestive Handbook of Practical School Method. The authors, in a small section on corporal punishment which remained unrevised for over thirty years, stated that there were a few scholars for whom a little corporal punishment was the best and only effective corrective. Irregular punishment, such as boxing ears, thumping backs and rapping knuckles, was harmful and injudicious. Proper corporal punishment inflicted without vindictiveness was very beneficial for the correction of misdeeds and had been known to yield the best results in securing the happiness of the offender and of the class in general [T.A. Cox and R.F. MacDonald,

The Suggestive Handbook of Practical School Method, Blackie & Son, London and Glasgow, 1913, p.22].

An additional text used during the 1940s (and into the 1950s) for the training of Queensland teachers,

Learning and Teaching: An Introduction to Psychology and Education, concentrated on the psychological aspects of corporal punishment. The authors, A.G. Hughes and E.H. Hughes, pointed out the psychological weaknesses and dangers of using corporal punishment. They put forward the abolition of corporal punishment as an ideal to work towards and stated that some schools managed without its use. They also pointed out the factors which made it difficult to achieve this ideal in some schools, for example accommodation and size of classes. The authors stated that corporal punishment should be used only for serious offences, that irregular methods should not be used and that teachers should observe the regulations relating to its use [A.G. Hughes and E.H. Hughes,

Learning and Teaching: An Introduction to Psychology and Education, Longmans, Green & Co., London, 1937, pp.190–1].

In the 1960s and 70s, there was a proliferation of American and British text books on methods of teaching which were used in Queensland tertiary institutions. In these, additional research evidence was presented in support of the abolition of corporal punishment, but many of the texts supported its use for serious offences when all other methods have failed.